Introduction: Art Therapy for Chronic Illness

Art therapy for chronic illness has become the cornerstone of my daily life. Living with severe Secondary POTS from a PONS stroke caused by EDS, along with PPPD, polyplopia, tinnitus, and small fiber neuropathy, I’ve had to redefine what it means to be productive, expressive, and fulfilled. Art is no longer just a hobby—it’s my lifeline, my structure, and my way of staying connected to the world.

My Daily Routine: Listening to My Body’s Rhythm

Most days begins early, usually between 4 and 6 a.m., with a cup of green tea and a podcast to ease into the morning. I outline my goals, respond to emails, and play a few light games on my iPad to warm up mentally. If I’m able, I dive into digital programming work until around 8 or 9 a.m., followed by tending to my indoor juicing greens garden and a green juice.

Physical movement is essential, so I fit in a 45-minute workout and, if possible, some yard work or gardening before lunch. After eating, I do a light 20-minute workout while watching a show, then rest with a nap from 1 to 4 p.m. Evenings are reserved for creative work—painting, woodworking, piano improvisation—if my body allows. Dinner is followed by another short workout, and I wind down with art or TV before bed around 11 p.m.

I don’t choose my activities—my body does. Some days I’m bedridden, others I’m functional but slow-moving. On rare “good” days, I can tackle more demanding creative tasks like painting or building.

Do you use an adjustable bed or special pillows for sleep?

Art as Therapy: A Future to Look Forward To

Art gives me something to look forward to, even when I’m stuck in bed. It helps me through emotional lows by offering a sense of purpose and continuity. I can think about future projects and reflect on past ones with pride.

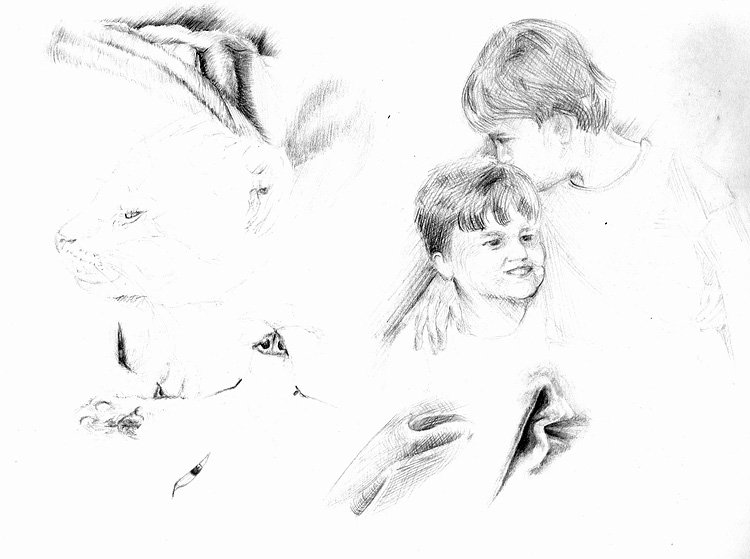

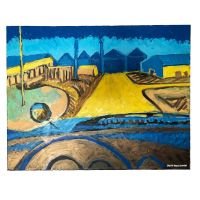

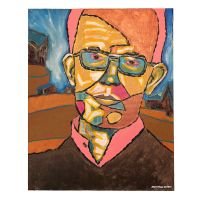

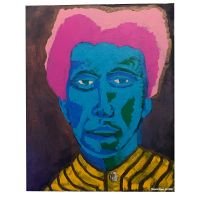

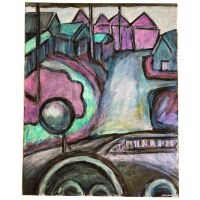

Since becoming disabled, art has shifted from being a skill or job to becoming the central focus of my life. I now prioritize quick, finished projects—one-day paintings, short programming sprints, or small design tasks. Long-term projects are difficult due to fatigue and sensory overload, so I break everything into baby steps. I use broad strokes in painting and rely on creativity rather than detailed reference work, which is hard on my eyes and neck.

Physical Challenges: Adapting to Limitations

Creating art with my conditions requires constant adaptation. My workspace is clutter-free and always ready, so I can start or stop without prep or cleanup. This helps me conserve energy and avoid unnecessary strain.

Sensory overload, especially visual, is a major challenge. I take frequent eye breaks and monitor tinnitus, which often signals when I’m pushing too hard. Auditory projects are less overwhelming, but physical pain in my hands, arms, and neck limits my ability to play instruments. I’ve lost access to guitar and saxophone, but I still find joy in occasional piano improvisation.

Emotional Impact: Finding Flow and Connection

When I’m making art, I enter a zone where emotions fade and focus takes over. It’s a meditative state that helps me forget the pain and limitations around me.

My websites—GnarlyTree.com and Sketchbooks.org—are my way of staying connected to the world. They allow me to share my journey and support others, even when I can’t participate physically. The grief of losing certain activities is softened by the abundance of creative outlets I still have.

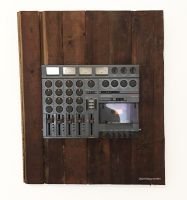

Digital Creativity: Building with Purpose

GnarlyTree.com and the revival of Sketchbooks.org were born from a need to feel fulfilled during long hours in bed. I began experimenting with AI-assisted programming in 2023, which helped me relearn languages like JavaScript and PHP. This opened the door to creating meaningful digital spaces that reflect my personal journey.

Programming and design are ideal for my condition—they allow for small, incremental progress that adds up over time. Even on bad days, a single completed task can make the day feel worthwhile. Both sites are deeply personal: I live with POTS, and I’ve filled dozens of sketchbooks with thousands of drawings over the years.

Advice and Reflection: Redefining Success

To anyone newly diagnosed with POTS or EDS who feels creatively blocked, I’d say: start small. Draw in a journal. Let the process be the therapy, not the product.

I’ve learned that art is an activity, not an object. I rarely sell my work—it piles up in boxes or goes on my walls—but the act of creating is what heals. Success, for me, is having others enjoy what I’ve made and sticking to the daily habits that support my health. Exercise and diet are hard work, especially since I wasn’t active before becoming ill, but I’m trying. That’s success.

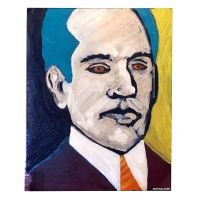

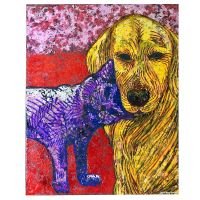

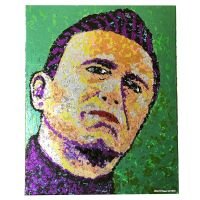

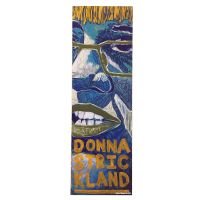

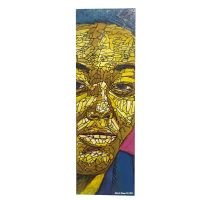

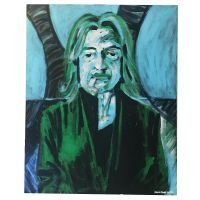

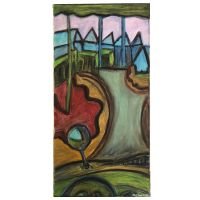

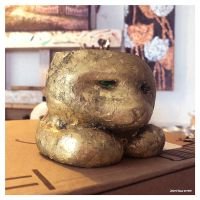

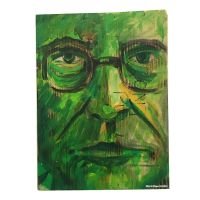

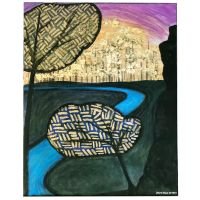

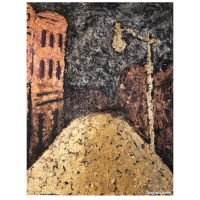

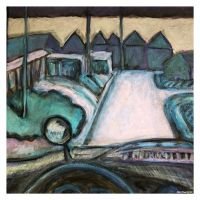

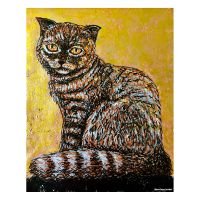

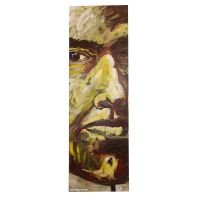

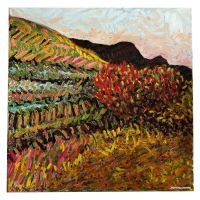

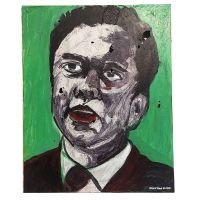

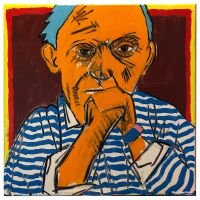

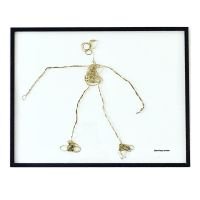

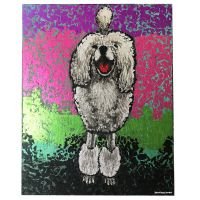

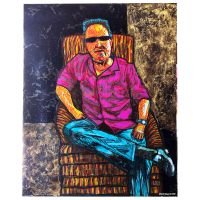

Art Therapy | Small Bit of My Artwork